The Black Pirate

Directed by Albert Parker, Story by Elton Thomas, Adapted by Jack Cunningham, Photographed by Henry Sharp, Starring Douglas Fairbanks and Billie Dove. Internet feed provided by the Internet Archive.

Commentary by Film Historian Anthony Slide Along with Robin Hood (1922) and The Thief of Bagdad (1924), The Black Pirate is the most entertaining and spectacular of all the films of Douglas Fairbanks, produced between 1915 and 1934. He produced, wrote (using his familar pseudonym of Elton Thomas), supervised the direction, and starred; and The Black Pirate perfectly illustrates the fun-loving, almost childlike quality of his personality. The film is not intended as historical reality but is rather an amalgam of all the children's volumes that deal with piracy and adventure. One should not make the mistake of taking the film seriously, and certainly the conclusion with the Fairbanks character revealed not as a pirate but a nobleman is typical of other films of the period, such as Valentino's The Sheik.

Adding substantially to its commercial potential, The Black Pirate is one of the first major films to be shot in the early, two-color Technicolor process, although Fairbanks demanded a somewhat more subdued image than was usual. While modern prints fail to show the original color to advantage, they do illustrate the basic problem with the two-color process; it used only two primary colors, red and green, and could not reproduce the color blue, something of a disadvantage with for a movie with an ocean background. There is no fault with the presentation here; both the sky and the sea can only photograph green. Yes, Fairbanks appears to have performed all his own stunts, including the most spectacular, that of slicing the canvas sail of the ship and sliding down. No, aside from the climactic rescue filmed off Santa Catalina Island, The Black Pirate was not filmed on location, but rather at the Pickford-Fairbanks Studios, later the Goldwyn Studios and still in operation, in West Hollywood, in the summer of 1925. Here, Fairbanks filmed the underwater rescue without the aid of water, but with the extras suspended on wires and making swimming motions against a painted backdrop. Evidential of the film's occasional borrowing from Peter Pan, one contemporary critic compared the extras to "a bunch of fairies."

Douglas Fairbanks and his second wife, Mary Pickford, were the acknowledged king and queen of Hollywood, reigning from a palace they called Pickfair. The 1933 divorce was way in the future, and as proof of the affection the two felt for each other, Pickford substitutes from leading lady Billie Dove in the final sequence in which the hero and heroine embrace. Pickford did not want her husband kissing another woman. When the couple came to London in 1920, they were mobbed by fans, received with more enthusiasm than the British Royal Family, and it is therefore appropriate that one day before the U.S. opening, The Black Pirate received its London premiere at the Tivoli Theatre on March 7, 1926. The Los Angeles premiere at Grauman's Egyptian Theatre on May 8,1926, honored both Hollywood's king andqueen, with The Black Pirate sharing the screen with Pickford's latest film, Sparrows.

Soon Mary Pickford was to cut off her curls, "bob" her hair and become part of America's flapper age. Similar, the Fairbanks persona, his characterizations and performances, heralded a new modern age for the country, wherein all was possible and the keywords were accomplishment and success.

Commentary by Wright State University Maritime Historian Noeleen McIlvenna

This is a fun romp, but like any cultural artefact, it tells us more about the year it was made than the time it purports to explain. The movie is probably set in the Golden Age of Piracy, 1685-1715, as the British Royal Navy emerged as masters of the Atlantic. The previous century had seen British monarchs sponsor privateers (pirates with a license) such as Francis Drake and Walter Raleigh, but now that England's merchant marine dominated Atlantic shipping profits, their policy shifted against pirates.

We need to understand that the cruelties so marvelously portrayed in the movie were symptomatic of the time, when the harshest men on the high seas were British officers. Firstly to the enslaved people they regarded as cargoes, for the Golden Age coincides with a huge increase in the Atlantic Slave Trade. And secondly, to their own sailors, often press-ganged into service against their will and then treated barbarically with small rations and merciless whippings. It is in this context that men became pirates, starting in and around the Caribbean islands. They were people of all races and languages sharing a common goal of freeing themselves of one type of bondage or another. In the most accurate detail from the movie, the men did get to choose their own leaders, for as Marcus Rediker, the finest historian of piracy, tells us, "the pirate ship was democratic in an undemocratic age." They had a voice, better hours, more food and of course a bigger ration of rum. And the British settlers on the American side of the Atlantic loved how they brought goods tax-free, as Britain tried to enforce the new Navigation Acts which placed customs duties on many items.

So in 1698, Parliament passed 'An Act for the More Effectual Suppression of Piracy' and the Royal Navy devoted more resources to the capture of the pirates, with Blackbeard finally trapped around the Outer Banks of North Carolina in 1718. And in an ironic twist on Fairbanks movie, at least half of Blackbeard's crew were black pirates, trying to escape a life on a plantation. The Navy were not heroes.

Commentary by Maryland State Underwater Archaeologist and Adjunct Professor (Johns Hopkins University and St. Mary's College of Maryland) Susan Langley

In 1926, research and scholarship about pirates and piracy was scant (1) and largely an admixture of fable and fact. However, Fairbanks's flick is clearly tongue-in-cheek; crammed with all the popular cliches of pirate lore past and present. It would be difficult to undertake a serious critique of its historical accuracy even if such a thing was desirable because of the difficulty in pinpointing its era and geographic location from the film's vessels, costumes and piratical behavior.

The ships in the opening scenes appear to be 16th century based on the high stern and forecastles but the rescue row galleys at the end are very Mediterranean/North African xebecs from the 17th through early 19th centuries. The costuming is largely 17th to early 18th century for the "English" pirates, with their enemies/'victims' clothing appearing vaguely Hispanic. Overall the intent is likely aiming for the 17th-18th centuries; the Golden Age of Piracy, which is most broadly defined as 1650 to 1730 with some scholars circumscribing it more narrowly as 1690 to 1726-30. However, the pirates' behavior is out of synch; their initial cold-blooded murderous behavior being more closely associated with their violent 19th-century reaction to a significant crackdown on piracy globally; this is when the dead-men-tell-no-tales attitude became more widespread. While there were always pirates who were notorious for their especially brutal behavior, such as Edward Low, Christopher Condent, and Francois L'Olonnois (2), generally behavior through time varied with geographic location and the nationality of the pirates. Indian, Chinese and Iberian-related (Spanish, Portuguese and South American) pirates had consistently more violent and brutal reputations through time, whereas European and North African pirates were usually less violent seeing the value in keeping ships unless they were too damaged or there were insufficient men to crew them and preferred to hold prisoners for ransom or sell them into slavery (3). This, of course, is the more enlightened position Fairbanks convinces the pirates is an improvement on their profit in order to save the situation. In fact it would have been the norm.

A further reflection on increasingly violent behavior over time is the famous walking the plank. Until the 19th century there was only one known incident and it involved British mutineers forcing their officers to walk the plank, not pirates. This was a confession in Newgate Prison by George Wood to a chaplain in 1769. There are three other cases; one in 1822 and two in 1829 that were the actions of pirates and all occurred in the Caribbean. So at present there are only four documented incidents of this "typical" pirate activity. Equally rare was the burying or other hiding of treasure. While there are a handful of recorded situations, most pirates did not trust each other sufficiently and generally spent their share as soon as they were able. In addition documented "loot" rarely included large treasure hoards and pirates frequently were as happy to acquire food stores, clothing, dyestuffs, ammunition, and particularly alcohol. A final thought on fact and fancy is Fairbanks's riding his knife down the height of a sail, not once but three times. While Fairbanks's his own stunts including this one, the television program Mythbusters posits it would not be possible with actual ship-grade sailcloth and that either the sail was of a lighter material or had been cut and stitched to permit easy cutting. Also, in the associated scene the swivel guns, while fairly accurate in design, would not have been paired, but it looks really cool.

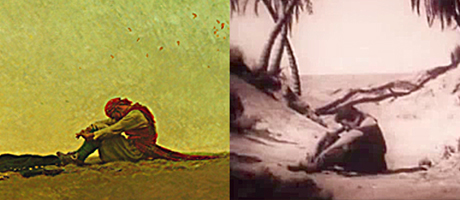

What is more fun than nit-picking the film for its historical short-comings, is to look at its imagery. Since it was Fairbanks's vehicle, either he was having fun with his research or showing excellent business and marketing acumen in replicating scenes from popular pirate literature of the time, such as Ralph D. Paine's pirate serial of 1922 and Howard Pyle's Book of Pirates (1921), an assemblage of materials previously published in widely read magazines like Harper's and popular boys' journals. Another painter emulated on the celluloid is Pyle's student Frank Schoonover. Immediately after the Scene Card "Marooned," Fairbanks is seated in the exact position of the subject of Pyle's 1909 painting of the same name (below, close-up). There are other images and scenes echoing Pyle's and Schoonover's paintings; the challenge to the reader is to find others:

Marooned (detail), 1909 Howard Pyle (1853-1911) Oil on canvas 40 x 60 in. (101.6 x 152.4 cm) Delaware Art Museum, Museum Purchase, 1912

www.delart.org and still image taken from The Black Pirate.

In many ways, the film Pirates of the Caribbean (2003) is very much an homage to The Black Pirate, a paean to pirate lore in general, and just as tongue-in-cheek overall. Two classic examples among many are the protagonists' single-handed immobilizing of a vessel by fouling the rudder, for which there is no analogous historical event, and the similarities, even to a level of silliness, between the underwater scenes. While there are excellent examples of more realistic period pirate films (4), a good swashbuckler can't be beat and should just be enjoyed on that level.

Citations:

1 An exception is pirate historian Philip Gosse, who edited Captain Charles Johnson's, A General History of the Pyrates. Cayme Press, Kensington 1925.

2 Condent and Low (Charles Ellms. 1856. Pirates Own Book. Frances Blake: Portland, ME Pgs. 223-224; 232, respectively). L'Olonnois (David Cordingly, editor. 1998. Pirates, Terror on the High Seas. JG Press, North Dighton, MA Pgs. 44-45.)

3 North African pirates/corsairs (really privateers for the Beys of the Barbary Coast states) raided as far as Baltimore, Ireland and several places in Iceland, notably the Vestmannaeyjar islands expressly for the purpose of capturing Christians to sell as slaves in North Africa and the Middle East until/if they were ransomed, for a double profit. This action worked both ways with the Knights of St. John at Malta raiding Muslim states for slaves to sell at Leghorn (now Livorno), Italy.

4 The Light at the Edge of the World 1971 (Yul Brenner, Kirk Douglas, Samantha Eggar) however set in 1865 it post-dates the last pirate hung in the U.S. by 3 years.

Previous Next